A group of activists has tried to prove that yes, with a strange protest in Washington: but there are many disturbing precedents

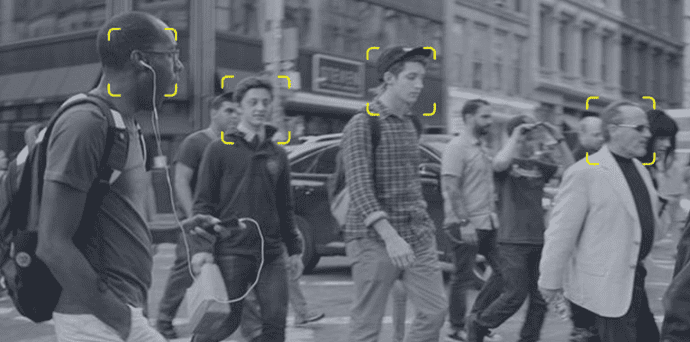

A group of U.S. activists used software to photograph and recognize the faces of some 14,000 people in Washington, D.C., to demonstrate the risks and limitations of facial recognition related to security and surveillance, and the dangers of this technology in the absence of specific legislation.

On Thursday, November 14, three people in white overalls and with a smartphone on their forehead walked the streets and halls of Capitol Hill, the seat of the United States Congress, framing the faces of the people they crossed. Their phones were connected to Amazon’s facial recognition software, Rekognition, a very sophisticated system that is sold, among other things, too many police forces in the United States. The program uses algorithms that improve as more and more faces are cataloged and recognized, and recently Amazon announced that it has further enhanced the system, adding a function to detect people’s moods. In a few hours, the three activists collected thousands of faces. They compared them with a database that allows their identification, which in some cases was able to identify the people they were framed immediately. The whole process was streamed.

In their action, the activists, who are part of the online rights organization Fight for the Future, said they had identified a Congressman, seven journalists, 25 Amazon lobbyists and even a celebrity, singer Roy Orbison, who died in 1988, thus highlighting one of the main problems of facial recognition: in many cases, the technology is wrong. Washington residents will also be able to upload their photos to the organization’s website to see if they were recognized during the action.

Although the activists’ suits had a “facial recognition in progress” warning on them, they did not ask people’s consent, and their phones automatically recognized anyone passing by. The legality of their operation is the main problem: at the moment, there is no law preventing people from storing facial recognition data without the consent of the person being photographed. The organization has indicated that all data collected will be deleted after two weeks, “but there is no law on that. At the moment, sensitive facial recognition data can be stored forever”.

In a press release, the group said their message to Congress was simple: “Make what we did today illegal.” “It’s terrifying how easy it is for anyone, a government, a company, or simply a stalker, to set up large-scale biometric monitoring,” said Evan Greer, deputy director of Fight for the Future. “We need an immediate ban on the use of facial surveillance by law enforcement and government, and we should urgently and severely restrict its use for private and commercial purposes as well. Their action was part of the BanFacialRecognition.com campaign, which has been endorsed by over thirty major civil rights organizations, including Greenpeace, MoveOn and Free Press.

Several U.S. cities have already openly banned facial recognition technology, including San Francisco, Somerville (Massachusetts), Berkeley and Oakland (California), and the issue also entered the presidential election campaign when Bernie Sanders called for a total ban on the use of facial recognition software for police activities last August. Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, and Julián Castro – other Democratic Party primary candidates – said they wanted to regulate it.

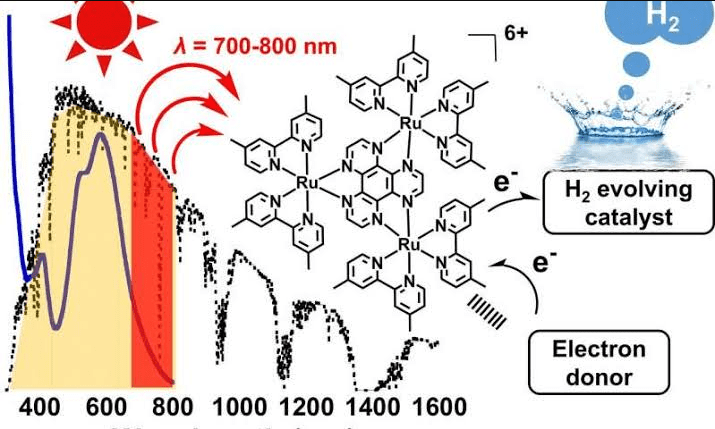

Recognition and other similar systems have already created several controversies in the United States. Amazon employees have protested against the sale of the technology to the authorities, and frequent misidentification has been reported, particularly about the recognition of the faces of people of certain ethnic groups. Some studies have found that recognition in major software has an error rate of 1% when analyzing light-skinned men, and up to 35% in cases of black women. This is because worldwide, the artificial intelligence behind artificial recognition systems have been developed mainly with data from white or Asian men. According to the New York Times, one of the central databases used by facial recognition systems contains over 75% of men’s faces and over 80% of white faces.

This asymmetry has already caused significant incidents for companies in the industry: in 2015, Google had to apologize publicly after its Google Photo app recognized gorillas in photos of some black people. The main concern, of course, has to do with exchanges of people and the fact that technology could increase discrimination against certain groups.

Supporters of the use of these systems, even by the police, say there could be several advantages in investigating and searching for missing persons. Still, the arguments against this are more numerous and stronger. Woodrow Hartzog and Evan Selinger, respectively professor of law and professor of philosophy, argued in a 2018 article that facial recognition technology is inherently harmful to the fabric of society: “The mere existence of facial recognition systems, which are often invisible, damages civil liberties because people will act differently if they suspect they are under surveillance.

Luke Stark, a digital media scholar, working for Microsoft Research Montreal, has also brought another argument in favor of prohibition. He compared facial recognition software to plutonium, the radioactive element used in nuclear reactors: for Stark as the radioactivity of plutonium derives from its chemical structure, the danger of facial recognition is intrinsically and structurally embedded within the technology itself because it attributes numerical values to the human face. “Facial recognition technologies and other systems to visually classify human bodies through data are inevitably and always means by which “race,” as a constructed category, is defined and made visible. Reducing humans into readable and manipulable sets of signs has been one of the hallmarks of racial science and administrative technologies dating back several hundred years. The simple fact of classifying and numerically reducing the characteristics of the human face, according to Stark, is therefore dangerous because it allows governments and companies to divide people into different races, to build subordinate groups, and then to reify that subordination by referring to something “objective”: finally claiming subordination “as a natural fact.”

China is already using facial recognition with this objective in Xinjiang, an autonomous region in the northwest of the country inhabited mainly by the Uighurs, an ethnic Muslim minority accused by the Chinese government of separatism and terrorism whose members are systematically persecuted and locked up in “re-education” camps. The system has been called “automated racism” by the New York Times. Instead of starting from the assumption that facial recognition is possible, says an article by Vox on the subject, “we would do better to start from the assumption that it is forbidden, and then isolate rare exceptions for specific cases where it might have justification.”