Journalist Mike Murphy, who deals with technology for Quartz, wrote on Twitter: “I experience a lot of new technology for work, and it’s rare that I’m entirely affected by something new. With Mixhalo it happened, and I think it will change the way we participate in live events.

Mixhalo is an app developed by a startup of the same name, made to allow those who participate in an event – for now mainly musical, but possibly also of another kind – to have a better and “more immersive” experience. In the case of a concert, Mixhalo asks spectators to connect to the app and put on headphones, offering them the chance to hear the music as the person playing it on stage does, and also to decide how to listen to that music.

One of the founders of Mixhalo is Mike Einziger, guitarist of Incubus, an alternative metal band whose most famous song is “Drive,” which was released in 1999 and whose refrain says, “Whatever tomorrow brings / I’ll be there, I’ll be there.” Murphy wrote that he first tried Mixhalo at an Incubus concert in New York, along with all the other viewers, and that he had “a live music experience like never before.”

With Mixhalo I could hear the musicians’ mix coming straight from the stage, in the same way, they heard it. I could choose to listen to a specific blend, moving between the parts with guitars or excluding the channel with the voice of singer Brandon Boyd […] I could turn the volume up or down and jump from one channel to another as, when and how much I wanted. I was in the audience, in a lateral sector, but it was as if Incubus were playing just for me. […] I could understand what Boyd was singing and hear the drums distinctly.

With Mixhalo, Murphy wrote, it doesn’t matter where you are while attending the concert or if the venue has poor acoustics: “Wherever you are, you can have perfect sound. Marc Ruxin, the company’s CEO, told Venues Now, “We’re trying to democratize music: we want every place to be the best possible place. Ruxin compared what Mixhalo wants to do to live music to what high definition has done to TV images: “Consumers have been enjoying low definition for decades, until something better came along: TV with HD is nicer, and music with Mixhalo sounds better. While it’s understandable that this possibility excites musicians for a living, it doesn’t necessarily mean that ordinary people will have the same reaction to using an app during a concert and – amid all the confusion – adjusting volumes and choosing tracks. All this, however, to a live music concert to listen to only through headphones, and with the mediation of a smartphone.

Maybe also for this reason, Mixhalo doesn’t want to deal only with music: its app can also be used when you attend a sports event (to hear a chronicle or interact in various ways with what you are seeing), at a conference (for example to hear the real-time translation of what someone is saying in a foreign language) or even at the theatre.

Despite this, for now, music remains Mixhalo’s main interest, and it is no coincidence that it was founded by Einziger and his wife Ann Marie Calhoun, a well-known violinist, famous among other things for her collaborations with the composer Hans Zimmer. Einziger explained to Quartz that he was one of the first musicians to use, around 2000, special headphones – in-ear monitors – that allowed him to hear, while he was playing, only the sounds coming from the stage, i.e., excluding all the remaining noises. So he began to think it was strange that “from stage one had a completely different hearing experience from that of the audience.”

Einziger said that the “real epiphany” came to him in 2016, when at rehearsals for a Grammy performance he made one of his guests listen to how the music was heard by those who played it from the stage, a privilege that is usually given to a few people: to use Einziger’s words, only to the “frontman’s girlfriend.”

Taking advantage of some knowledge he had made while studying at Harvard about ten years before, during a break in Incubus, Einziger got in touch with some people who, looking at the matter from a technological point of view, assured him that what he had in mind could be done. Einziger also said that he had some blessing from Elon Musk, who became interested in the project before he had even left and said: “If you can do it, it will change things.”

The natural part was developing an app. The hard part – as anyone who has tried to use the internet at a concert knows – was to make sure that the sounds could reach every audience in real-time and in excellent quality.

Without getting too technical, Mixhalo uses what Tech Radar calls a “private wi-fi network.” Whenever at a concert you want the audience to use Michael, you first have to install a series of antennas capable of transmitting all the audio channels that are recorded on stage. Before the concert, spectators must then download the app, equip themselves with headphones or earphones, and then connect to the private wi-fi network created by Mixhalo’s antennas. This is a particular type of wi-fi network developed specifically by Mixhalo, but as Quartz writes, “on closer inspection, it looks a lot like a radio signal.”

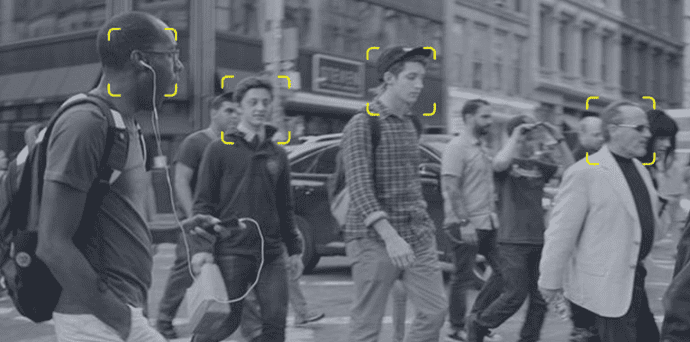

According to Simpson, Mixhalo’s local signal works so well that, as with the radio signal, “the first person to connect will have the same experience as the ten-thousandth. In the case of a standard wi-fi signal, there is a constant flow of data sent and received, because “when we listen to a song on Spotify, the network needs to know where we are and if we are moving.” With Mixhalo, however, there is almost only data going to the connected devices. Some of the data have to be sent from smartphones anyway because Mixhalo needs to know where a viewer is so that the audio arrives at the exact moment they would hear it if they didn’t have headphones.

Simpson said she is convinced, talking to Quartz, that Mixhalo is ready to support dozens of audio channels during the same concert and that technically it could also handle up to 150 different channels, many more than a philharmonic orchestra. More than the number of channels, at the moment, the discriminating price that Mixhalo asks to those who want to use the technology at their events is the size of the area: the bigger it is, the more antennas are needed to ensure a good signal to everyone. But Simpson says that, however, setting up the antennas is not a more complicated process in itself than setting up the lights or speakers for that same concert.

So far, no orchestra has used Mixhalo, but among those who have experimented with the app – generally with satisfactory results and many appreciations – were Aerosmith and Metallica. Mixhalo also recently signed a contract for future collaboration with the Staples Center in Los Angeles, which hosts hundreds of events a year, including the Lakers’ basketball games and the Kings’ ice hockey games.

Speaking of possible extra-musical evolutions of Mixhalo, the company remains somewhat vague, but an app downloaded by most of the participants of the same event can satisfy different needs. The simplest things are telerecording and communication through apps of information, data, and statistics in real-time. But theoretically, an app like Mixhalo can be used to do real-time surveys (perhaps during a conference) or – in the case of sporting events – to place bets. Another important aspect is security: Mixhalo could be used to send relevant messages or alerts to all viewers.