With his unscrupulous trade policy Trump has managed to get the Chinese government to a first deal, but there is one but.

It was a good week for US President Donald Trump’s trade policies. On Monday the Wall Street Journal, the country’s leading economic newspaper, hosted an article in which its financial adviser Peter Navarro details why, according to him, Trump’s “unorthodox” policies on international trade have proved to be a great personal success for his president and the country. Two days after the article was published, a Chinese delegation led by Vice President Liu He signed a trade agreement that should be the first step towards the end of the war of duties and counter-duties triggered by Trump two years ago.

The preliminary agreement is particularly favourable to the United States, as the Chinese Government is committed to purchasing around $200 billion a year in US products. In contrast, US sanctions affecting Chinese products will remain in place until the impact of the new agreement signed this week is assessed. In short, it seems that Navarro was right: Trump’s bizarre and unorthodox trade policy, criticized by all the significant economists, once put into practice has proved more effective than expected. China has succumbed to his pressure; the American economy continues to go quite well and does not seem to have suffered the setback that many feared.

As many have noted in recent days, however, Trump’s victories hide at least a couple of problems. The agreement with China, although somewhat favourable to the United States, has not solved the underlying issues in the trade relationship between the two countries, the reasons behind Trump’s decision to start the “trade war” with China. At the time, Trump had two objectives. The first was to counteract the Chinese Government’s subsidies to export industries, a strategy that the Chinese Government adopted so that it could export competitively priced products and displace competition. The second: to protect the intellectual property of American companies, which the Chinese often manage to violate by requiring companies that want to establish themselves in China to make joint ventures with local companies and to share their patents.

With this week’s agreement, none of these objectives has even been touched upon. The Chinese Government has committed itself to buy on the American market, but for the moment, it does not seem to have any intention of changing its industrial policies. The members of the Trump administration themselves had repeated in recent weeks that the agreement, which is now being finalized, would not resolve all trade disputes between the two countries. The deal has been renamed “phase one”: a sort of first half of the negotiations which, according to the Trump administration, will continue in the coming months.

For the most critical, this week’s agreement only serves to repair some of the damage caused by the trade war itself and prevent more from being done, but it is not intended to resolve the root of the problem. The Chinese Government, they say, will probably wait for the outcome of the next presidential elections before deciding what is really at stake, and for the time being will be content with the current situation where the risk of new duties has been averted. In order to find out who is right, we need to look in detail at how the trade war unfolded, and try to find out exactly who ended up paying the duties that the two countries have imposed on each other over the last two years.

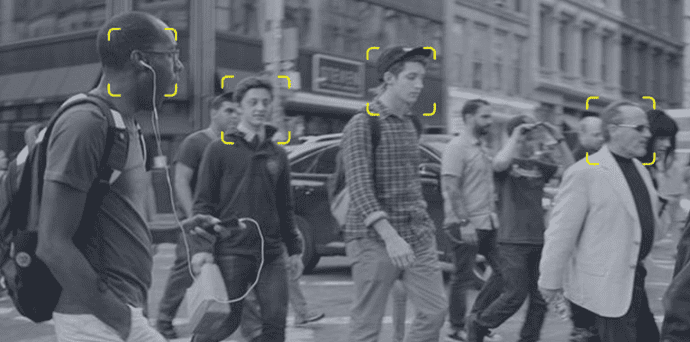

That Trump was hostile to China and considered its trade unfair was known since the 2016 presidential campaign. Once he got to the White House, however, it took Trump about a year to get serious. The first tariffs were approved in early 2018 and then, between pauses, backward marches and rises, they grew for the next two years. Today the United States is imposing additional tariffs on 360 billion dollars of Chinese products exported to the United States. These tariffs can reach up to 25 percent of the price of the product, and affect a number of goods in whose production China has long specialized, such as solar panels, batteries and electronic components (a total of 1,300 products).

In response, China has imposed tariffs on as many American products, particularly agricultural and food products, such as pigs, nuts, fruit and soybeans, but also aeroplanes, aluminium and steel tubes. In short, with the trade war, it has become more expensive for industries and consumers in the two countries to buy export products from the rival power. What effect has all this had on the economies of the two countries?

There are two possibilities in these circumstances. The first is that industries in the country subject to the duties choose to give up part of their profits to keep their prices competitive (in this way they “pay” the tariff imposed on them themselves). Second: products subject to duties continue to be purchased at the higher price (e.g. because there are no substitutes) or are replaced by more expensive products locally or in countries not subject to duties (more costly in this case means more costly than the product purchased initially before tariffs). In the latter case, it is the country that has put the tariffs in place that pays the cost.

According to numerous studies published in recent months, the trade war started by Trump so far has been paid for mainly by US consumers and businesses. Those who import Chinese products subject to tariffs have continued to do so, and have unloaded the increase in their costs either by raising prices to consumers or by cutting their profits. In other cases, the replacement of a Chinese product by one manufactured in the US or another country not subject to the duties has led to a price increase for consumers.

For supporters of the duties, such as Navarro, these are not significant problems. In the medium and long term, the increased demand for US-produced products (which have become comparatively cheaper due to the duties) will stimulate investment in those sectors, which in turn will lead to increased production and thus lower prices. In the short term, however, this phenomenon has yet to occur. According to research published in the leading journal of the National Bureau of Economic Research, for example, “about 100 per cent” of the cost of tariffs put in place by the Trump administration is currently paid by US companies and consumers.

Another problem with the effectiveness of Trump’s trade war is the substantial difference between the impact of the tariffs ordered by Trump and those imposed in response by China. Most of the duties ordered by Trump affect high-tech Chinese products: mobile phones, TV sets and other electronic components, none of which are easy to replace (some responsibilities change to steel, but China is only the tenth exporter to the US, so the measure has not had a particularly strong effect).

China, on the other hand, has put many tariffs on American agricultural products for which it is easy to find new suppliers. Chinese importers were able to quickly replace soya imported from the US with Brazilian soya, for example, incurring a slight price increase but at the same time causing significant damage to US farmers. For the time being, therefore, the United States has managed to bring China to the negotiating table, but in return, they have had to pay an increase in the price of several imports.

For the US economy, which is still stable and very strong, the backlash of tariffs has not been a significant problem. At the same time, China is in a situation that many observers see as more delicate and precarious. Despite this, however, the practices of the Chinese Government, which caused the start of the trade war have not been changed and do not appear to be changing shortly.